Were there traditionally been 'two Frances': the Catholics and the revolutionaries, whose confrontation until the middle of the last century

Introduction

The notion of “two Frances” - Catholics and revolutionaries - is an oversimplification of a complex historical reality, but it does capture some key tensions that shaped French society and politics from the French Revolution until the mid-20th century.

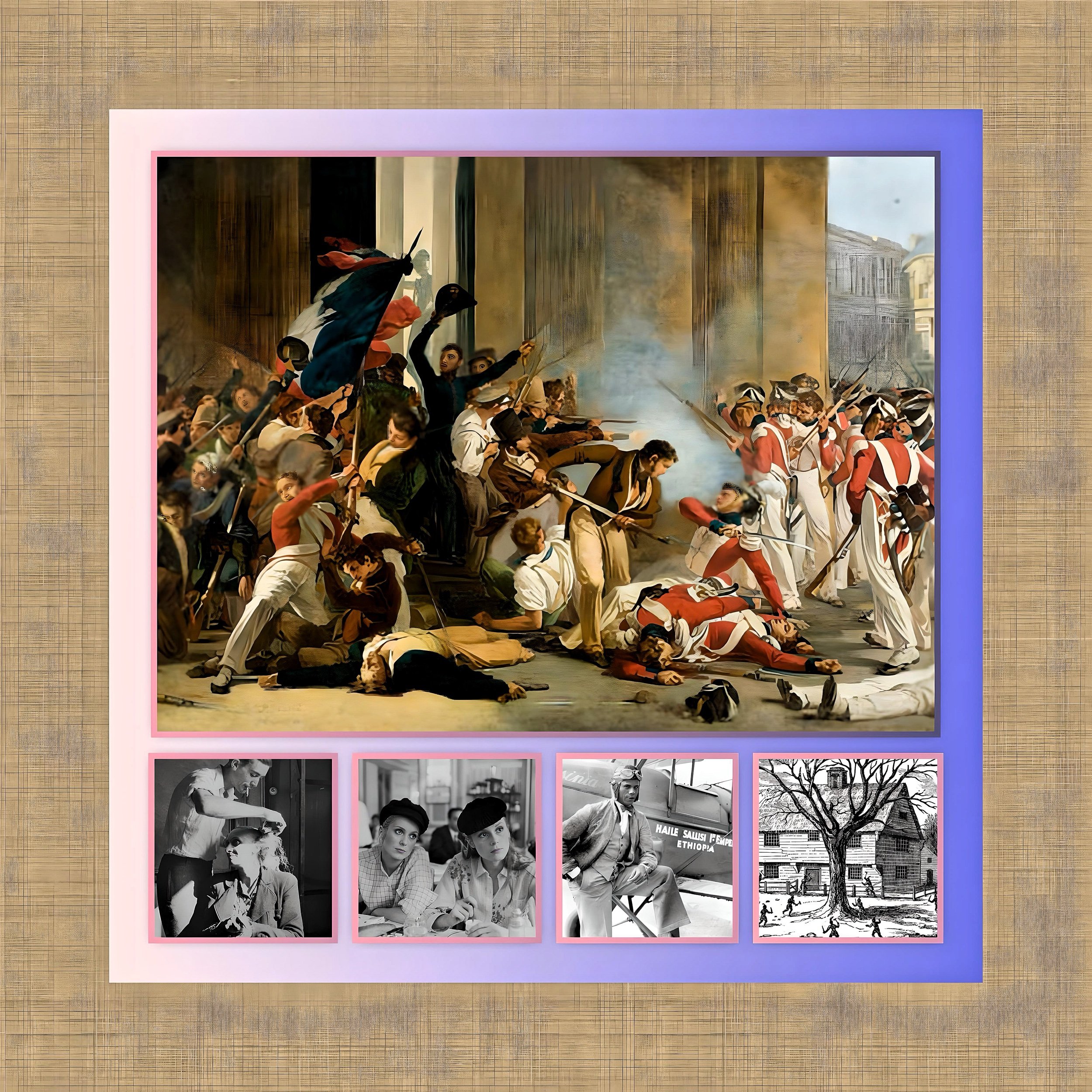

The French Revolution and Religious Conflict

The French Revolution of 1789 marked a dramatic turning point in the relationship between the Catholic Church and the French state:

The revolutionary government seized Church property, abolished religious orders, and required clergy to swear an oath of loyalty to the state.

A campaign of dechristianization was launched, including the destruction of religious symbols, closure of churches, and establishment of new civic cults.

Many clergy and devout Catholics resisted these measures, leading to persecution and violence against the Church.

This created a deep divide between supporters of the revolutionary ideals and those who remained loyal to the Catholic Church and the old order.

Ongoing Tensions in the 19th and 20th Centuries

The conflict between Catholic traditionalists and secular republicans continued to shape French politics long after the Revolution:

Napoleon’s Concordat of 1801 attempted to reconcile the Church with the state, but tensions persisted.

Throughout the 19th century, there were periodic clashes between Catholic conservatives and anticlerical republicans.

The separation of church and state in 1905 was a major victory for the secular camp, but also intensified Catholic opposition.

Nuances and Complexities

While the “two Frances” concept highlights real divisions, it’s important to note some nuances:

Not all Catholics opposed the Revolution or republican values. Some sought to reconcile Catholicism with modern ideas.

The revolutionary/republican camp was not monolithic in its approach to religion. Views ranged from moderate anticlericalism to militant atheism.

Other factors like class, region, and political ideology also shaped these conflicts, not just religious beliefs.

By the mid-20th century, this divide had begun to lose its centrality in French politics, though some tensions remained.

Conclusion

The idea of “two Frances” captures important historical tensions, it should be understood as a simplification of a more complex and evolving relationship between religion, politics, and national identity in France.