The Dynamics of Great-Power Competition- Exploring New Spheres of Trump’s Influence in a Complex World

Introduction

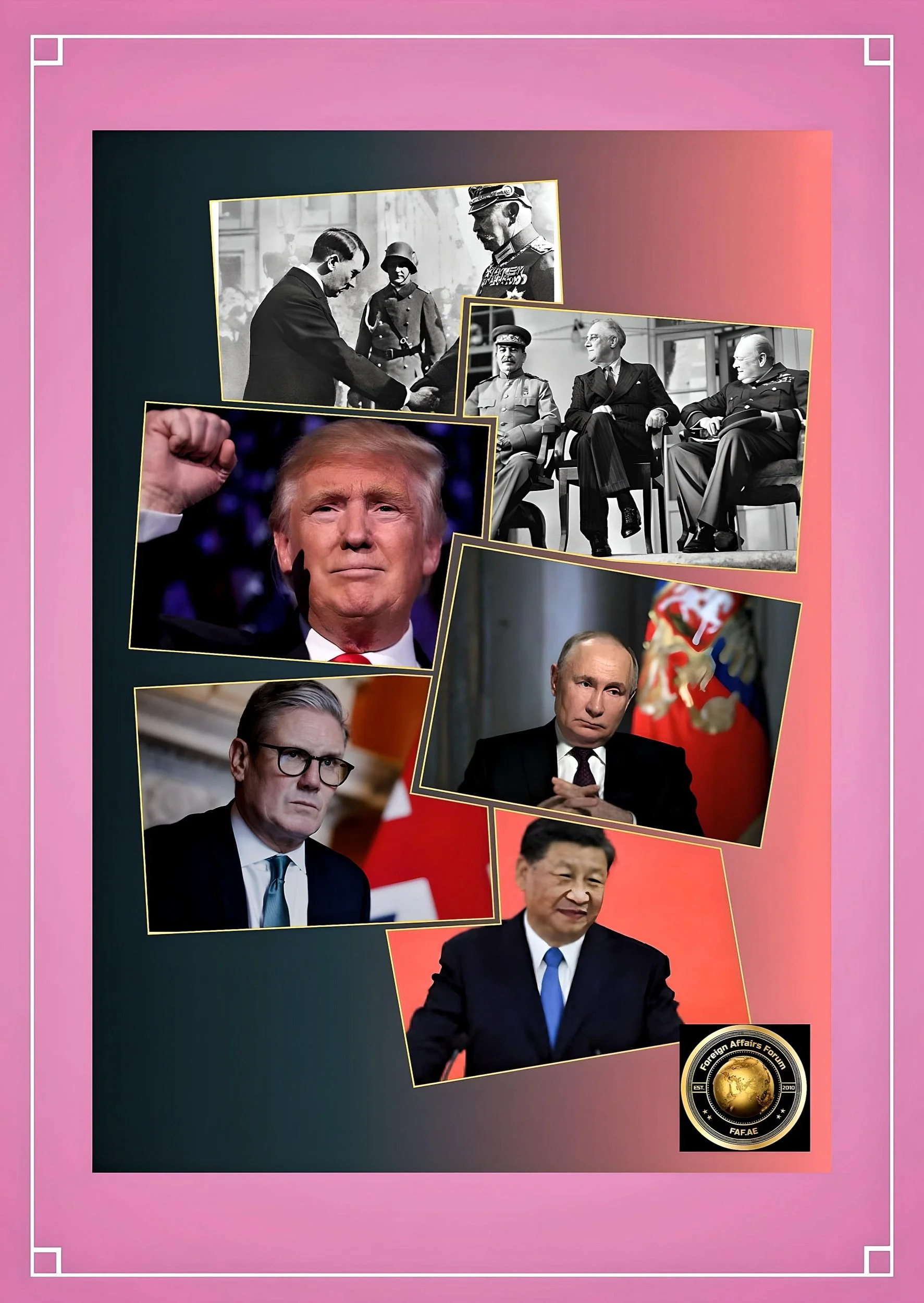

The proclamation that “great power competition returned” in Trump’s 2017 National Security Strategy marked a significant shift in American foreign policy that has now evolved into something more transformative – a rejection of the post-WWII liberal international order in favor of distinct spheres of influence.

With Trump’s return to the White House in 2025, what began as a bipartisan consensus on competing with China and Russia has morphed into a fundamentally different vision of world order that resembles 19th-century great power politics more than the alliance-based system that defined American leadership for decades.

The Historical Arc of Great Power Competition

Great power competition is far from new—the historical norm in international relations.

The struggle for supremacy between dominant states dates back to the late 4th millennium BC when early civilizations in Egypt and Mesopotamia vied for regional dominance.

Throughout history, the rise and fall of great powers has followed recognizable patterns, with economic strength translating into military power and geopolitical influence.

From the 1500s to the mid-1700s, Great Britain and France contested economic supremacy in a mercantilist system.

The 19th century saw competition between Britain and several rising powers, while the 20th century witnessed the United States surpassing Britain as the dominant global power.

Research on past eras of great power competition demonstrates that a majority involved power transitions among dominant states, with three-quarters culminating in or featuring destructive periods of violent conflict.

For those claiming great power competition “returned” in the 2010s, the post-Cold War era represented an anomaly – a brief unipolar moment when American power stood largely unchallenged.

One international relations scholar noted, “Competition among great powers cannot return because it never really went away.” What changed was not the underlying reality of competition but America’s strategic framing of its relationships with China and Russia.

From Cooperation to Competition

The Shift in U.S. Strategy

While the Trump administration formalized “great power competition” as an organizing principle for U.S. foreign policy in 2017, the shift from counterterrorism toward great power rivalry had been underway for some time.

This evolution began during the Obama administration with Hillary Clinton’s “pivot to Asia,” which provided a strategic justification for reducing American commitments in the Middle East.

Trump’s 2017 National Security Strategy articulated this shift explicitly, arguing that the post-Cold War assumption that “engagement with rivals and their inclusion in international institutions and global commerce would turn them into benign actors and trustworthy partners” had “turned out to be false.”

The document identified China and Russia as “revisionist powers,” challenging America’s geopolitical advantages and attempting to reshape the international order in their favor.

When Biden took office in 2021, despite dramatic changes in other aspects of U.S. foreign policy, the focus on great power competition remained.

Biden’s approach emphasized working through alliances and multilateral institutions to counter China and Russia, while Trump favored more unilateral and transactional methods.

Biden’s 2022 National Security Strategy maintained the competitive framing, describing “powers that layer authoritarian governance with a revisionist foreign policy” as “the most pressing strategic challenge” to America’s vision.

Trump’s New Spheres of Influence Doctrine

Trump’s return to the White House in 2025 has marked a significant evolution beyond the bipartisan consensus on great power competition.

Rather than simply continuing to compete within the existing international system, Trump has moved toward a more fundamental restructuring of global order around distinct spheres of influence.

This approach represents a departure from the post-WWII liberal international order that the United States helped establish and has led for over seven decades.

In this vision, Trump’s United States does not automatically include traditional allies like the EU and NATO member states within its sphere of influence.

Instead, the administration appears to be “recentering on the northwestern hemisphere, with the core American area of influence composed of North and Central America, Greenland, and only a sliver of Western Europe.”

This narrower conception of America’s sphere aligns with Trump’s long-standing skepticism of distant alliances and his transactional approach to international relations.

The most apparent manifestation of this new doctrine has been Trump’s provocative statements about expanding direct American control within its hemisphere.

He has repeatedly expressed interest in annexing Canada, purchasing Greenland, and seizing control of the Panama Canal – objectives that treat friendly nations as “weak interlocutors and impediments to be subdued.”

While shocking to traditional foreign policy experts, these ambitions appear consistent with a 19th-century conception of spheres of influence that emphasizes territorial control rather than alliance networks.

Trump and his advisors seem to view this approach as a logical response to a changing world order. One analysis notes, “Trump wants the US to secure its sphere of influence for the 21st century.

Embracing spheres of influence also implies that the US may not spend American lives blocking another power from securing a sphere of influence”. This willingness to concede spheres to rival powers represents a dramatic departure from previous American policy, which sought to prevent any hostile power from dominating key regions.

Parallels with Rival Powers’ Approaches

Trump’s affinity for spheres of influence aligns him more closely with the worldviews of Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping, who have long advocated for great power prerogatives in their respective regions.

As one analysis states, “Trump is the first US president to openly share Vladimir Putin’s contempt for the principles of the rules-based order.

They believe great powers should enjoy spheres of influence in their neighborhood and think smaller countries should kowtow to the local hegemon”.

This philosophical alignment has translated into policy shifts regarding key flashpoints. In Ukraine, Trump’s administration has offered concessions to Russia and backed away from Ukraine’s territorial integrity.

Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth stated in February 2025 that a return to Ukraine’s pre-2014 borders was “an unrealistic objective” and that attempting to regain all territory “will only prolong the war.”

Similarly, Trump has shown “relatively little interest in Taiwan,” viewing it primarily as “a chip to play in the larger US-China relationship.”

This approach could have profound practical implications. One analysis warns, “It would likely spell the end of Ukraine’s independence and bring the Russian threat closer to Western Europe.

Taiwan would quickly lose its autonomy, and China would take a significant step towards dominating Asia”.

While competition with China continues in economic and technological domains, with increased tariffs and restrictions on semiconductor imports and AI software, geopolitical competition appears to be dividing the world into distinct spheres.

Challenges to Implementation

Despite Trump’s apparent embrace of spheres of influence, significant obstacles stand in the way of fully implementing this vision.

Perhaps most ironically, as one analysis points out, “the Trump administration is currently doing everything possible to destroy the sphere of influence it already has.”

By treating traditional allies with hostility, imposing tariffs on neighbors, and questioning security commitments, Trump risks undermining the regional dominance his doctrine seeks to solidify.

The Munich Security Conference in February 2025 “did profound damage to European trust in the US,” with senior administration officials showing “disdain for European political norms and ambivalence — at best — about NATO.”

Similarly, America is “alienating its Northern and Southern neighbors with tariffs, threats, and insults.” These actions undermine rather than strengthen America’s sphere of influence, as “there is no conceivable US sphere of influence that excludes Europe, Canada, and Mexico.”

Domestic constraints also limit Trump’s ability to implement his vision entirely. Any dramatic actions to “cede spheres of influence to Russia in Europe or China in East Asia” would “run into a huge amount of resistance in his bureaucracy, in Congress, in the media.”

The deep institutionalization of America’s global commitments creates significant inertia against radical changes in foreign policy.

Finally, the international system's multipolar nature makes neat divisions into spheres of influence increasingly difficult.

The European Union, India, Japan, and other middle powers maintain significant autonomy and are unlikely to accept subordination to any great power’s sphere.

Globalization has created complex interdependencies that cross regional boundaries, and the clean separation of the world into distinct spheres faces practical and ideological challenges.

Implications for the International Order

The shift toward spheres of influence under Trump’s second presidency represents a significant challenge to the liberal international order of the post-WWII era.

By prioritizing great power prerogatives over international norms and institutions, this approach undermines core principles underpinning global stability, including respect for sovereignty, peaceful resolution of disputes, and multilateral cooperation.

Trump’s actions have weakened key international institutions that the United States helped build.

In early 2025, his administration “significantly scaled back U.S. involvement with the United Nations,” withdrawing from the Human Rights Council and the UN climate damage fund, halting funding to the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees, and rejecting the UN’s 2030 Sustainable Development Goals.

Trump also withdrew the U.S. from the Paris Agreement and the World Health Organization, sanctioned the International Criminal Court, and questioned NATO commitments.

These moves reflect a broader rejection of the post-WWII international architecture in favor of more direct expressions of American power within a narrower sphere.

As Trump demonstrates an increasing willingness to intervene in areas beyond traditional presidential authority—from arts and sports to private companies and local governance—his presidential style increasingly resembles an imperial executive rather than a constitutional leader constrained by checks and balances.

The implications extend beyond America’s immediate sphere.

By legitimizing spheres of influence as an organizing principle for international relations, Trump’s approach emboldens similar claims by Russia and China.

The growing alignment between these two powers, “animated by shared grievances against the configuration of the international order,” poses significant challenges to U.S. interests and its allies.

As these autocratic powers deepen their ties and collaborate more closely, the world risks fragmenting into competing blocs reminiscent of earlier great power rivalry.

Conclusion

Assessing the Sustainability of Spheres of Influence

Trump’s shift from great power competition to spheres of influence represents a fundamental challenge to the post-WWII international order that the United States helped create and has led for over seven decades.

While presented as a pragmatic adaptation to changing global realities, this approach raises serious questions about its sustainability and consequences.

Historical evidence suggests caution. Studies of past significant power transitions reveal that three-quarters culminated in or featured destructive conflicts.

The absence of agreed rules and institutions to manage competition increases the risk of miscalculation and escalation.

Treating international relations as a zero-sum game in which spheres must be defended against rivals, Trump’s approach may inadvertently increase global instability.

Moreover, by undermining alliances and international institutions while narrowing America’s sphere of influence, this approach may weaken rather than strengthen the United States’ global position.

One analysis notes, “If the US and Europe no longer share values, if the US is not a trustworthy security partner for Europe, and if it treats the European Union (EU) as an economic adversary, Europe has no reason to align with the US.”

The sustainability of this approach will ultimately depend on whether it can adapt to the realities of a complex, interdependent world where neat divisions into spheres of influence face both practical and normative challenges.

While the shift from cooperation to competition appears firmly established in American foreign policy, the further evolution toward distinct spheres of influence remains a contested territory in the ongoing struggle to define the future international order.