The Expansion and Fall of the Russian Empire: From Imperial Growth to Soviet Formation

Introduction

The Russian Empire’s journey from 1800 to its eventual collapse and transformation into the USSR represents one of history’s most significant geopolitical shifts.

This period witnessed dramatic territorial expansion, ambitious imperial leaders, devastating wars, and revolutionary change that redefined Eurasia’s political landscape.

FAF examines the empire’s expansion, the monarchs who drove it, and the complex factors that led to its demise and the subsequent formation of the Soviet Union.

Territorial Expansion of the Russian Empire (1800-1917)

By the dawn of the 19th century, the Russian Empire had already established itself as a vast territorial entity spanning from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Black Sea in the south and from the Baltic Sea in the west to Alaska, Hawaii, and California in the east.

This formidable landmass would continue to grow through strategic conquests and diplomatic maneuvers throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Expansion into the Caucasus and Southwestern Frontiers

Russia’s imperial ambitions in the early 19th century were significantly focused on the Caucasus region.

In 1801, following the death of King Giorgi XII of Kartli and Kakheti, Emperor Paul incorporated part of the Georgian Kingdom into the Russian Empire, ostensibly to protect these Orthodox territories from Persian influence.

This move sparked conflict with Persia in 1804, culminating in Russia’s victory by 1813, forcing Persia to cede all of Georgia, Dagestan, and most modern-day Azerbaijan to Russia.

Throughout the first half of the 19th century, Russia continued its southwestern expansion at the expense of the Ottoman Empire, using Georgia as its base for operations in the Caucasus and Anatolian front.

The late 1820s proved particularly successful for Russian military campaigns in this region, strengthening Russia’s position as a European power.

Central Asian Conquests

The Russian Empire’s expansion into Central Asia intensified in the latter half of the 19th century. In 1865, Russia conquered much of Russian Turkestan and continued to add territory in the region as late as 1885.

This expansion became known as the “Great Game” – a strategic rivalry between the Russian Empire and the British Empire over influence in Central Asia. Britain became increasingly alarmed as Russia threatened Afghanistan and, by extension, British India.

Arctic and Far Eastern Territories

The empire’s northward expansion continued with the discovery and claiming of Arctic islands, including the New Siberian Islands from the early 18th century and Severnaya Zemlya (initially named “Emperor Nicholas II Land”), which was first mapped and claimed as late as 1913.

World War I Territorial Gains

During World War I, Russia briefly occupied a small part of East Prussia (then part of Germany), a significant portion of Austrian Galicia, and portions of Ottoman Armenia. However, these territorial gains would prove temporary as the empire faced internal collapse.

Imperial Leaders and Their Expansionist Policies

The Russian Empire’s territorial growth was driven by a succession of emperors who pursued expansionist policies while grappling with internal reforms and challenges.

Alexander I (1801-1825)

Alexander I ascended to the throne in March 1801 following the assassination of his father, Emperor Paul. His reign coincided with the Napoleonic Wars, and after initially suffering defeats, Russia emerged as a key player in Napoleon’s downfall.

Following this success, Alexander established the Holy Alliance, which aimed to restrain the rise of secularism and liberalism across Europe. Under his leadership, Russia strengthened its position as a European power and introduced education and legal system reforms.

Nicholas I (1825-1855)

Nicholas I came to power after suppressing the Decembrist revolt and focused on strengthening the Russian military and autocracy.

During his reign, Russian influence in Central Asia continued to expand. However, his military ambitions were later checked by defeat in the Crimean War (1853-1856), which exposed weaknesses in his regime and led to a period of reform.

Alexander II (1855-1881)

Known as the “Tsar Liberator,” Alexander II implemented the Emancipation Reform of 1861, freeing Russia’s 23 million serfs—the single most important event in 19th-century Russian history.

While domestic considerations primarily motivated this reform, Alexander II continued Russia’s expansionist foreign policy.

He modernized the Russian army and oversaw continued conquest in Central Asia.

His reign ended with his assassination by the Narodnaya Volya, a nihilist terrorist organization.

Alexander III (1881-1894)

Following his father’s assassination, Alexander III pursued reactionary policies, reviving the maxim of “Orthodoxy, Autocracy, and Nationality”.

A committed Slavophile, he believed Russia could only be saved from turmoil by isolating itself from Western European influences.

During his reign, Russia formed the Franco-Russian Alliance to contain Germany’s growing power, completed the conquest of Central Asia, and demanded significant territorial and commercial concessions from China.

Alexander III also promoted Russian nationalism and pursued a policy of Russification throughout the empire.

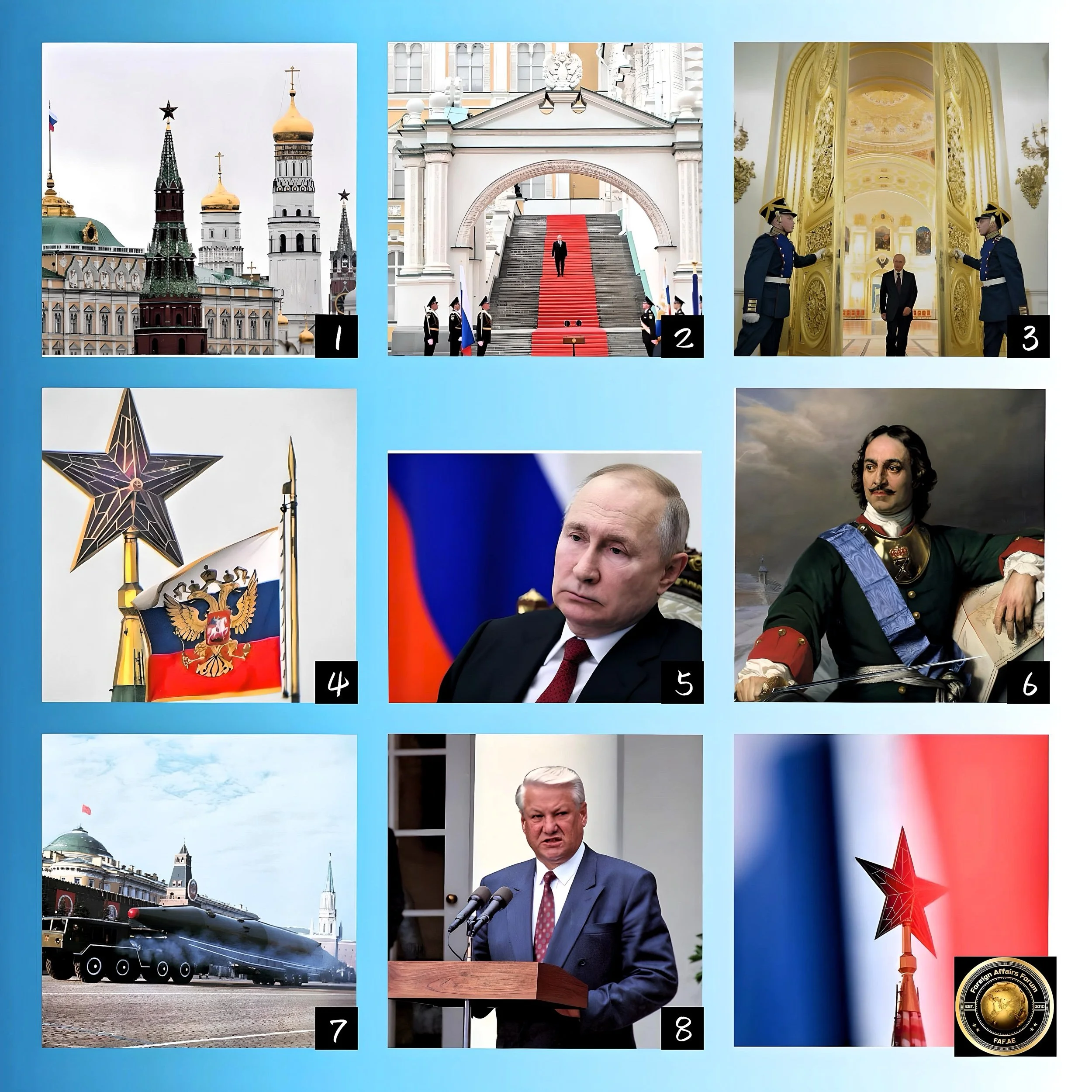

Nicholas II (1894-1917)

The last Russian emperor, Nicholas II, was committed to preserving the autocracy he inherited from his father.

Russia continued to expand during his reign, and the empire reached its territorial peak.

By the end of the 19th century, the Russian Empire dominated 22,800,000 km², making it the world’s third-largest empire.

However, Nicholas II’s rule was marked by significant setbacks, including defeat in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905 and growing internal unrest that culminated in the 1905 Revolution.

These events forced him to authorize the creation of a national parliament, the State Duma, though he retained absolute political power.

The Decline and Fall of the Russian Empire

Despite its vast territorial extent and great power status, the Russian Empire entered the 20th century in a perilous state, facing numerous challenges that would ultimately lead to its collapse.

Economic and Social Crises

The Russian famine of 1891-1892 killed hundreds of thousands and fueled popular discontent.

Though economic conditions improved somewhat after 1890 due to new crops like sugar beets and expanded railway access, Russia remained predominantly rural and poor.

The empire’s industrialization lagged behind Western European powers, creating significant economic disparities.

Political Radicalization

As the last remaining absolute monarchy in Europe, the Russian Empire experienced rapid political radicalization and the growing popularity of revolutionary ideas such as communism.

The Emancipation Reform of 1861 had unintended consequences. Freed peasants were burdened with special taxes and often received small amounts of unproductive land. This created ongoing rural discontent that revolutionary movements would later capitalize on.

The 1905 Revolution and Its Aftermath

The Revolution of 1905, sparked by Russia’s defeat in the Russo-Japanese War, forced Nicholas II to make limited concessions, including creating the State Duma.

However, these reforms failed to address fundamental issues within Russian society, and the tsar maintained his autocratic power, setting the stage for future revolutionary activity.

World War I and the Revolution

Russia’s entry into World War I proved catastrophic for the empire. A series of military defeats galvanized widespread opposition to the emperor.

The war strained Russia’s already fragile economy, leading to food shortages and increased hardship for the population.

In February 1917, mass unrest and military mutinies culminated in the February Revolution, which forced Nicholas II to abdicate and formed the Russian Provisional Government.

However, this government’s continued participation in the unpopular war and failure to address widespread food shortages resulted in further mass demonstrations.

In October 1917, the Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, overthrew the Provisional Government in what became known as the October Revolution. Nicholas II and the Romanov family were taken into custody and executed on July 17, 1918, bringing a definitive end to the Russian Empire.

Formation of the Soviet Union

Following the Bolshevik Revolution, Russia plunged into a devastating civil war between the communist Red Army and various anti-communist White forces.

After emerging victorious, the Bolsheviks established the foundation for the Soviet Union.

Establishment of the USSR

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) was officially created in December 1922, approximately five years after the Russian Revolution that ended the Tsarist Empire.

Vladimir Lenin, the architect and first leader of the Soviet Union, envisioned a multi-ethnic nation-state that would unite the formerly oppressed peoples of the Russian Empire in a country that was “national in form, socialist in content.”

Initially, the Soviet Union comprised six member states: Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, Azerbaijan, Armenia, and Georgia.

Over time, this expanded to fifteen republics as the USSR extended its influence into Central Asia and the Baltic states by 1940.

Lenin’s Vision and Early Soviet Structure

Lenin had denounced Tsarist Russia for holding Russians and non-Russians in what he called a “prison of nations.”

His new Soviet Union was intended to protect national identity while pursuing socialist economic and political systems.

However, the reality often differed from these ideals, as the USSR forced millions of people into a federation and eventually expanded to become the world’s largest country.

Factors Behind the Empire’s Collapse and Soviet Formation

The transformation from the Russian Empire to the Soviet Union resulted from a complex interplay of factors:

Military Failures and War Exhaustion

Russia’s defeats in the Russo-Japanese War and World War I severely undermined the legitimacy of the tsarist regime.

The continuing participation in World War I particularly angered the lower classes, creating fertile ground for revolutionary ideas.

Autocratic Rigidity

The Russian Empire’s failure to implement meaningful political reforms in response to changing social conditions contributed to its downfall.

Despite growing demands for democratic representation, Nicholas II clung to autocratic power, making revolutionary change increasingly likely.

Economic Inequality and Rural Poverty

Despite some economic improvements in the empire’s final decades, Russia remained predominantly agricultural and poor.

The unresolved land question and ongoing rural poverty created widespread discontent that revolutionary movements effectively harnessed.

Revolutionary Leadership

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, offered a compelling alternative vision based on Marxist principles that appealed to many Russians suffering under the old system.

Their organization and determination allowed them to seize power and establish a new political order.

Ideological Appeal of Socialism

The socialist ideas championed by the Bolsheviks promised to address Russian society's deep inequalities and create a more just system.

This ideological appeal helped the Bolsheviks gain support among workers, soldiers, and some peasants, particularly in urban areas.

Conclusion

The Russian Empire’s expansion from 1800 to the early 1900s transformed it into one of the world’s largest territorial entities, stretching across Eurasia from the Baltic to the Pacific.

Ambitious emperors, from Alexander I to Nicholas II, drove this expansion. They pursued territorial growth while struggling with the challenges of modernization and reform.

Despite its vast size and great power status, the empire’s internal contradictions—including economic backwardness, political rigidity, and social inequality—eventually collapsed during World War I.

The Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 ended over three centuries of Romanov rule and set the stage for the formation of the Soviet Union in 1922.

Initially comprising six republics under Lenin’s leadership, the USSR represented a radical departure from the imperial model, though it would eventually control most of the former empire’s territory.

While Lenin envisioned a multinational state protecting national identities while pursuing socialism, the Soviet Union’s development would follow a more complex and often contradictory path over its nearly 70-year existence.