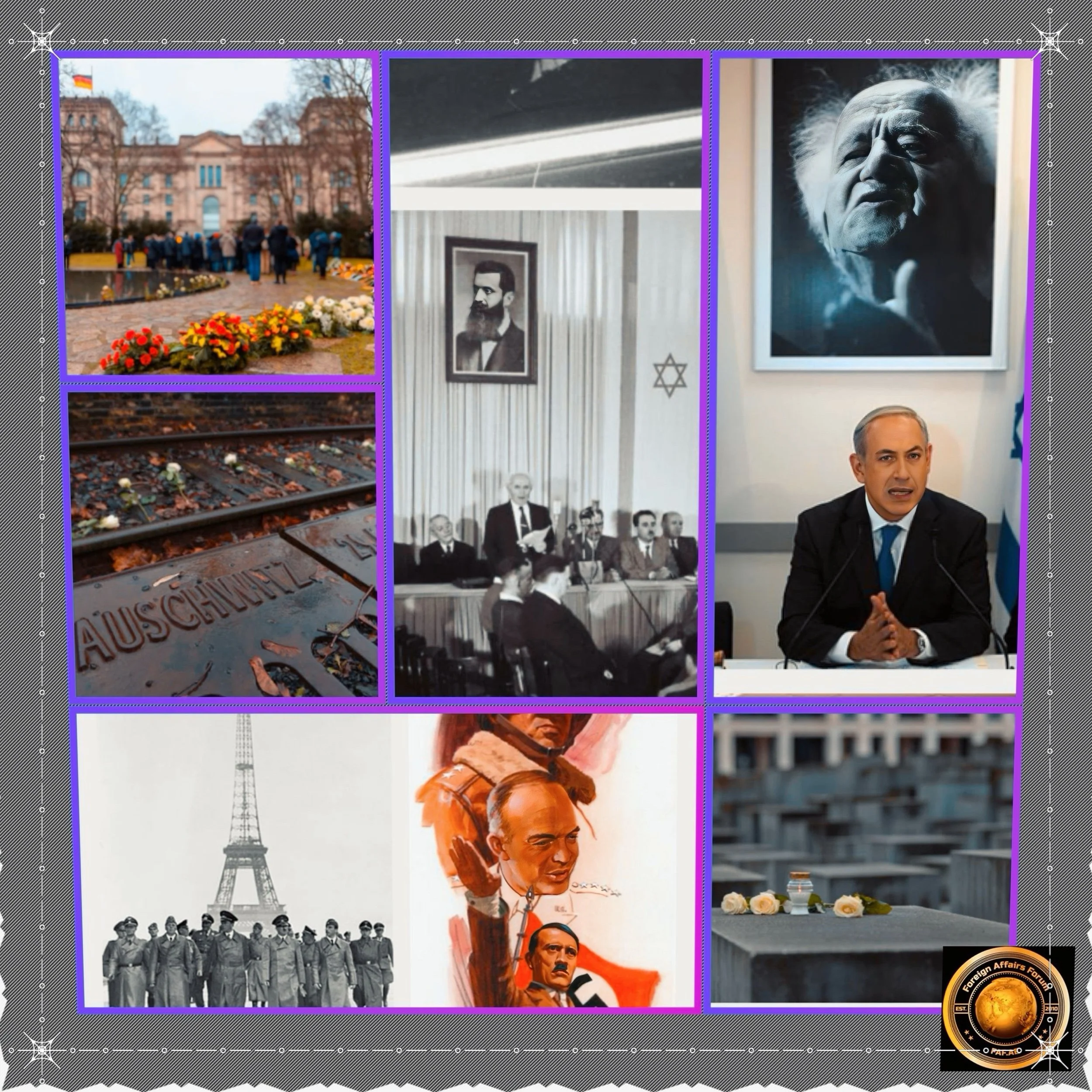

Immediate Post-Holocaust Actions: Israel’s Foundation and the Absorption of Survivors

Introduction

The Holocaust’s conclusion in 1945 left European Jewry shattered, with survivors facing displacement, trauma, and the urgent need for a secure homeland.

The establishment of Israel in 1948 emerged as both a response to this crisis and a culmination of Zionist aspirations. This analysis explores the immediate actions taken by Jewish leaders and international actors to address the survivors’ plight and lay the groundwork for a Jewish state.

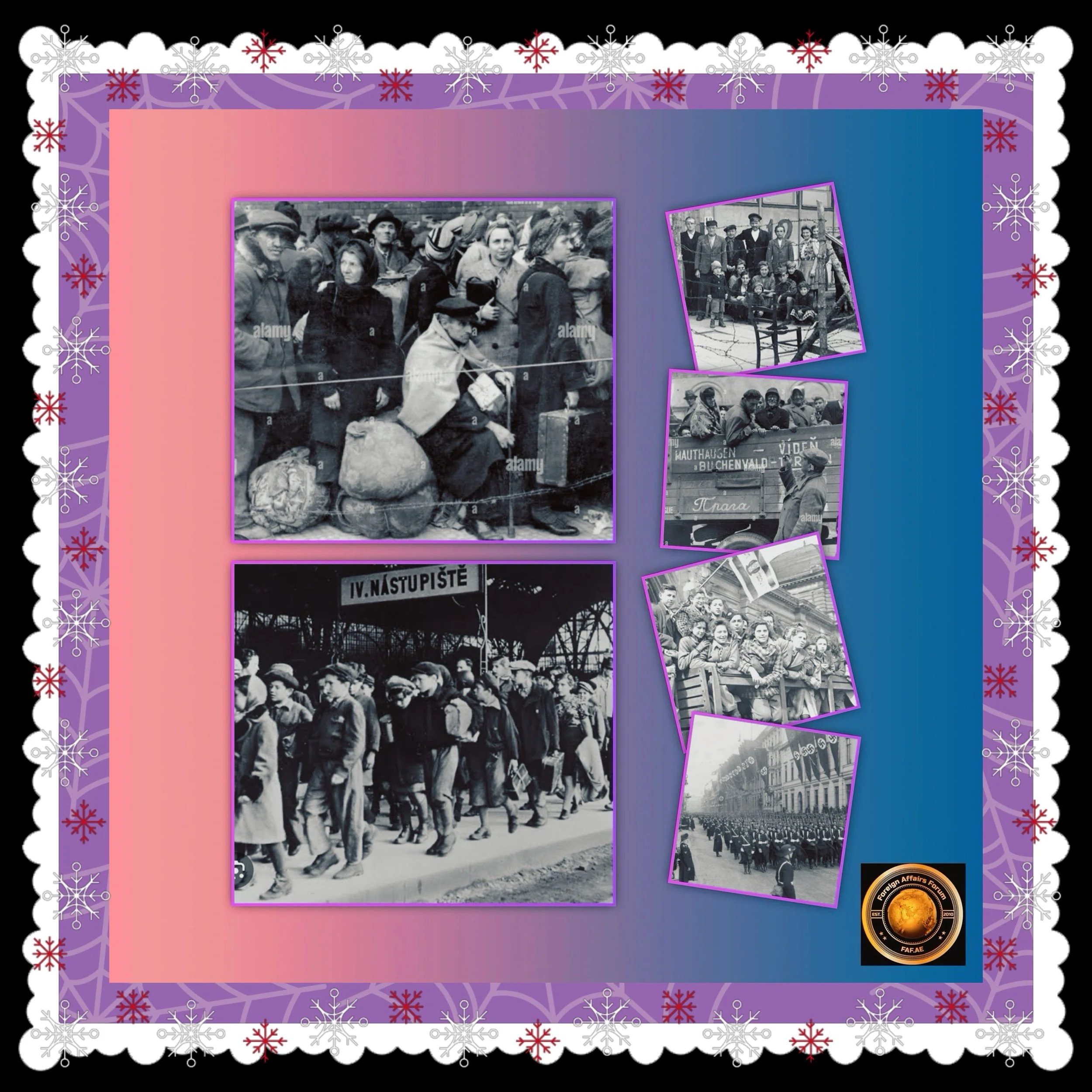

Refugee Crisis and the Displaced Persons (DP) Camps

Following liberation, approximately 250,000 Jewish survivors found themselves in Allied-occupied Germany, Austria, and Italy, housed in displaced persons camps such as Bergen-Belsen.

These camps, administered by the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) and Allied armies, became temporary sanctuaries but also symbols of ongoing instability.

Many survivors refused to return to Eastern Europe due to persistent antisemitism, exemplified by the 1946 Kielce pogrom in Poland, where rioters killed 42 Jews.

The DP camps evolved into hubs of Zionist activism, with survivors organizing protests and educational programs to advocate for mass immigration to Palestine.

David Ben-Gurion, leader of the Jewish community in Mandatory Palestine, visited these camps in 1945–1946, galvanizing survivors around the vision of a Jewish state.

His speeches transformed the DPs into a political force, with their demands for unrestricted immigration to Palestine becoming central to post-war diplomacy.

The Harrison Report of 1945, commissioned by U.S. President Harry Truman, condemned the squalid conditions in DP camps and urged Britain to issue 100,000 immigration certificates to Jewish refugees.

Though Britain initially resisted, international pressure mounted, particularly after the Anglo-American Committee of Enquiry corroborated these findings in 1946.

Immigration Challenges and the Briḥah Movement

British restrictions on Jewish immigration to Palestine, enforced through the 1939 White Paper, clashed with survivors’ desperation to leave Europe.

This tension catalyzed the Briḥah (“escape”) movement, a clandestine operation that smuggled over 100,000 Jews from Eastern Europe into Allied zones and DP camps between 1945 and 1948.

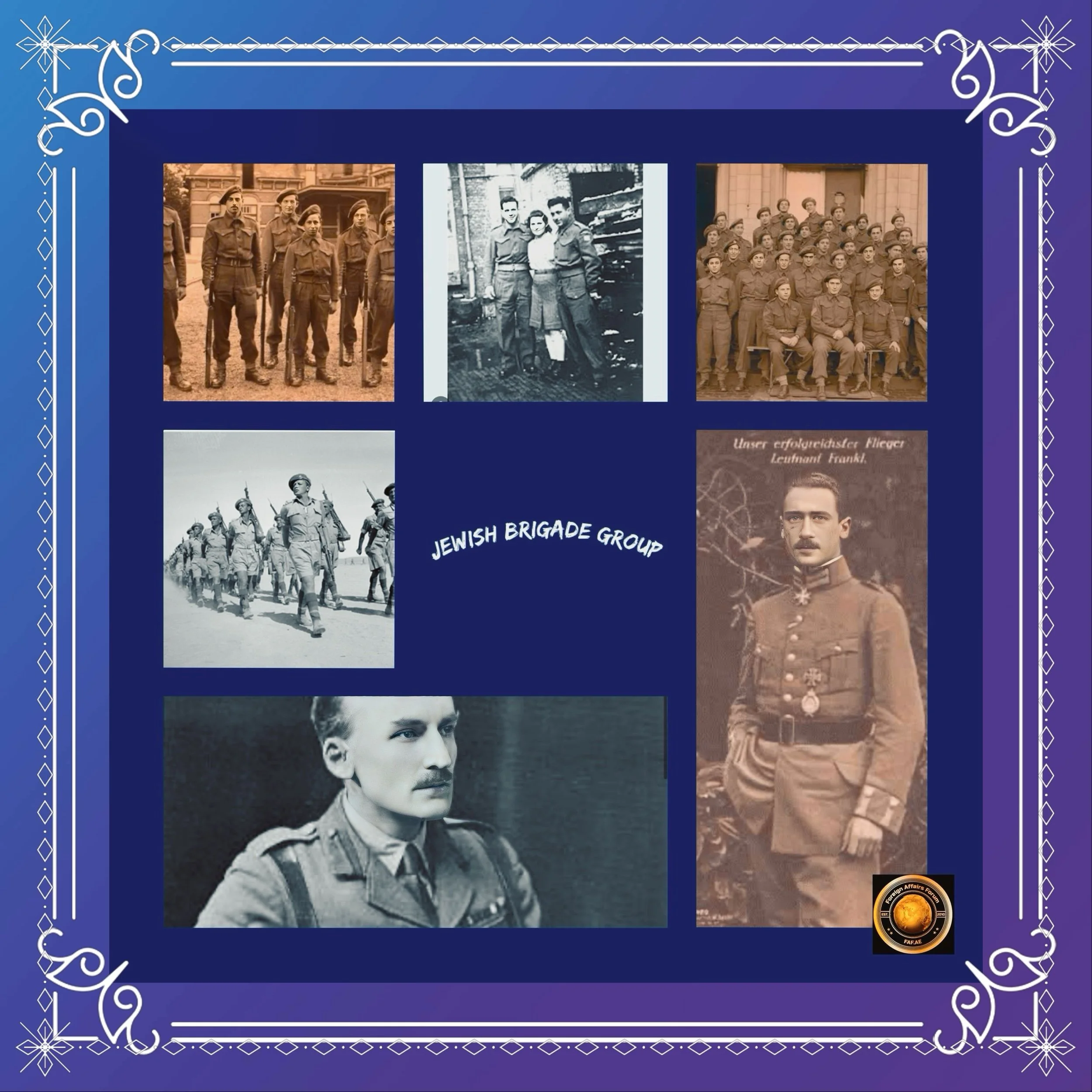

From there, the Jewish Brigade Group—a unit of Palestinian Jewish volunteers in the British Army—orchestrated illegal maritime journeys to Palestine.

Ships like the Exodus 1947, carrying 4,500 survivors, were intercepted by British forces, who diverted refugees to detention camps in Cyprus.

These efforts exposed the moral contradictions of British policy. While Britain had fought Nazi Germany, its refusal to admit Holocaust survivors into Palestine drew widespread condemnation.

The Exodus incident, in particular, became a rallying cry for Zionist causes, underscoring the urgency of establishing a Jewish state where immigration would be unrestricted.

International Diplomacy and the UN Partition Plan

The refugee crisis forced Britain to refer the Palestine question to the United Nations. On November 29, 1947, the UN General Assembly voted to partition Mandatory Palestine into Jewish and Arab states, a resolution accepted by Jewish leaders but rejected by Arab nations.

The plan allocated 55% of the territory to the Jewish state despite Jews constituting only one-third of the population. This decision reflected growing international sympathy for Jewish suffering post-Holocaust, as well as strategic Cold War considerations.

British withdrawal in April 1948 created a power vacuum, prompting Zionist leaders to declare independence.

On May 14, 1948, David Ben-Gurion proclaimed the State of Israel, invoking the Holocaust as a moral imperative: “The catastrophe which recently befell the Jewish people—the massacre of millions of Jews in Europe—was another clear demonstration of the urgency of solving the problem of its homelessness.”

The declaration pledged equality for all citizens, regardless of race or religion, though this ideal would face immediate challenges during the ensuing Arab-Israeli War.

Absorption of Survivors and Military Mobilization

Between 1948 and 1951, nearly 700,000 Jews immigrated to Israel, including two-thirds of Europe’s Jewish DPs. Holocaust survivors constituted over half of Israel’s military forces during the 1948 War of Independence.

Despite initial skepticism from native-born Sabras, survivors like Amnon Zilberspitz—a Hungarian Holocaust survivor killed in combat—proved instrumental in defending the nascent state.

Historians estimate that survivors comprised 40% of Israel’s combat troops, with their participation pivotal in securing victories such as the defense of Jerusalem.

Civilian absorption posed further challenges. Survivors established 45 agricultural settlements (kibbutzim and moshavim), doubling the population of these communities and contributing to Israel’s agrarian economy.

Organizations like the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee provided essential aid, while the Israeli government prioritized housing and employment programs, albeit with limited resources.

Legal and Political Foundations

Israel’s early legal framework sought to address both the Holocaust’s legacy and the realities of state-building. The 1950 Law of Return granted automatic citizenship to any Jewish immigrant, a direct response to the barriers Jews faced fleeing Europe during the 1930s–1940s.

Conversely, the Absentee Property Law (1950) confiscated land belonging to Palestinians who fled during the 1948 war, exacerbating tensions that persist today.

International reparations also shaped Israel’s economy. The 1952 Luxembourg Agreement with West Germany secured $715 million in compensation for Holocaust survivors, funds critical for infrastructure development and immigrant absorption.

However, this agreement sparked controversy, with figures like Menachem Begin condemning it as “blood money.”

Conclusion

Israel’s immediate post-Holocaust actions were defined by a dual mandate: to provide refuge for survivors and to assert Jewish sovereignty after centuries of persecution.

While the state’s creation offered a lifeline to displaced Jews, it also sowed the seeds of ongoing conflict with Palestinian Arabs.

The Holocaust’s shadow loomed large, informing Israel’s security policies and its national identity.

As survivors integrated into Israeli society, their experiences underscored a collective determination to prevent future genocides—a mission that remains fraught amid contemporary debates over occupation, human rights, and the ethical use of historical memory.

The interplay between Holocaust trauma and state-building reveals a complex legacy.

Israel’s foundational years were marked by resilience and innovation, yet also by compromises that continue to reverberate in the region’s geopolitics.

Understanding these immediate actions is essential to contextualizing Israel’s triumphs and ongoing struggles.