Brief on the history of nuclear weapons and US nuclear deterrent

Introduction

What is Nuclear deference?

Nuclear deterrence is the cornerstone of U.S. national security. It has provided the essential foundation for our defense strategy and safeguarded U.S. allies since 1945. It underpins every military operation undertaken by the United States.

The U.S. nuclear deterrent comprises a robust arsenal of atomic weapons and delivery systems, sophisticated nuclear command, control, and communications (NC3), along with the skilled personnel and critical infrastructure that sustain it all.

While we have not employed nuclear weapons since World War II, the United States actively leverages its nuclear deterrent daily to maintain global peace.

The nuclear age began with the use of the atomic bomb in 1945, spiraling into a nuclear arms race with the Soviet Union and reaching a peak with the last U.S. nuclear explosive test in 1992, marking the end of the Cold War.

In the post-Cold War era, our focus has shifted to effectively sustaining nuclear deterrent systems without further underground atomic testing.

2010 marked a significant change in the United States' nuclear posture. The 2010 Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) downplayed the role of atomic deterrents in our national security strategy, citing a perceived less dangerous security environment.

However, this assessment was misguided, as the security landscape has only become more competitive over the last decade.

The 2018 NPR drew attention to Russia's resurgence and China's emergence as strategic competitors and potential adversaries. In light of these unmistakable threats, the NPR emphatically underscored the urgent need for modernizing our nuclear deterrent.

Our strategic competitors have not stood idle; they have been actively modernizing, developing, testing, and deploying advanced systems for their nuclear deterrents for over a decade.

Russia is aggressively modernizing its nuclear arsenal alongside other non-nuclear strategic systems, which includes new road-mobile and silo-based intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs), advanced missiles, bombers, and cruise missiles.

Moreover, Russia is currently testing unprecedented nuclear capabilities, such as hypersonic glide vehicles, nuclear-powered and nuclear-armed cruise missiles, and nuclear-powered uncrewed underwater vehicles.

Simultaneously, China is modernizing and significantly expanding its robust nuclear forces, signaling the resurgence of Great Power competition.

China is diligently developing, testing, and fielding next-generation land-based ballistic missiles, enhancing the range of its submarine-launched ballistic missiles, and pursuing advanced bombers. It is also investing significant resources into advanced nuclear-capable systems and hypersonic vehicles, affirming its intent to compete globally.

Brief History of Nuclear Weapons

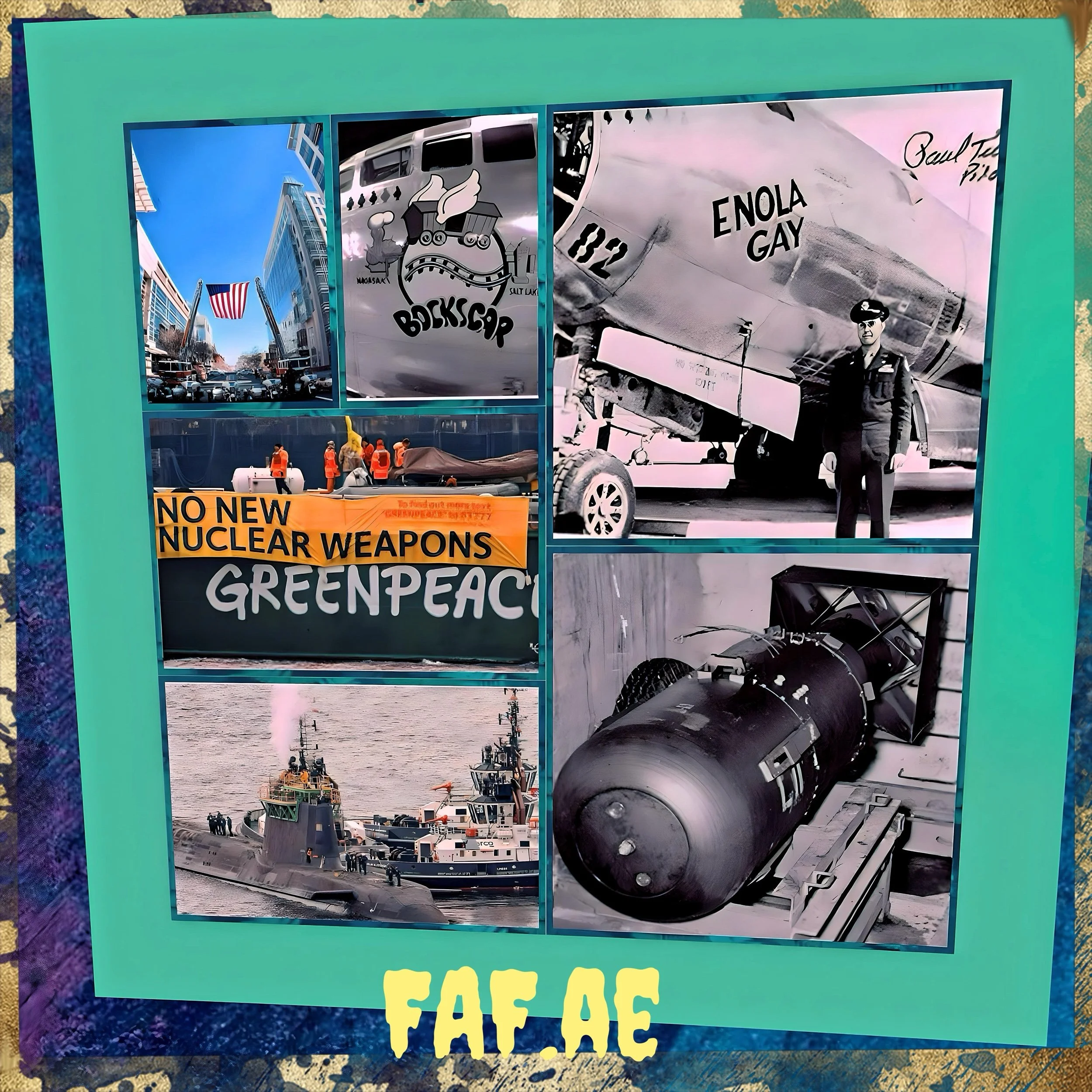

Aug 6th, 1945

On August 6, 1945, merely twenty-one days later, President Harry S. Truman authorized a specially equipped B-29 bomber, designated the Enola Gay, to release a nuclear bomb known as Little Boy over Hiroshima, Japan.

August 9th, 1945

‘The little boy’

Subsequently, on August 9, 1945, a second B-29 bomber, Bockscar, dropped another U.S. atomic weapon, Fat Man, on Nagasaki, Japan. These atomic bombs deployed on Hiroshima and Nagasaki represent the sole instances of nuclear weapons being employed in combat.

August 1949

By August 1949, the United States was no longer the exclusive nuclear power in the world, as the Soviet Union conducted its inaugural atomic device test during that month. Subsequently, the United Kingdom became the third nuclear weapons state, executing its first test in October 1952.

October 1952

The advent of nuclear weaponry played a crucial role in shaping the geopolitical landscape of the era. The two principal atomic superpowers, the United States and the Soviet Union engaged in a competitive race to innovate weapon designs and conduct nuclear explosive tests, thereby facilitating ongoing advancements in nuclear weapons technology.

In the nascent phase of the nuclear era, the U.S. atomic weapons program concentrated on the production of adequate nuclear materials to establish a substantial second-strike capability, allowing for a counter-attack following an all-encompassing initial strike. The United States also prioritized the deployment of atomic weapons across a broad spectrum of military delivery systems.

By 1967

By 1967, the U.S. arsenal had expanded to encompass over 30,000 nuclear weapons, a significant portion of which were classified as “tactical”—characterized by shorter ranges, lower yields, and non-strategic purposes—designed to counter the predominance of Soviet conventional forces, particularly in Europe.

After 1967

U.S. weapon systems were enhanced to facilitate improved operations and logistics for military operators; they incorporated modernized safety, security, and control features and augmented military performance characteristics, including selectable yields and increased accuracy. Additionally, the United States implemented substantial reductions in its stockpile of tactical nuclear weapons.

These transformations were facilitated by an advanced understanding of nuclear physics and weapon designs, particularly in the context of the Soviet Union. This led to a diminished emphasis on atomic armaments in the absence of a nuclear superpower rival.

With the nearly simultaneous cessation of both nuclear weapon production in 1991 and nuclear testing in 1992, the new challenge confronting the nuclear enterprise became one of maintaining and sustaining the legacy deterrent in the absence of new production or testing while also extending the operational lifespan of both weapons and delivery systems indefinitely.

In the same year, to actualize the "peace dividend" resulting from the conclusion of the Cold War, President George H.W. Bush mandated the withdrawal and destruction of ground-launched short-range missiles equipped with nuclear weapons, as well as the removal of all tactical nuclear weapons from surface vessels, attack submarines, and naval aircraft.

Since 1992-1994

In 1992, in anticipation of a potential comprehensive nuclear test ban treaty, the United States voluntarily suspended underground atomic testing.

The cessation of both new nuclear weapon production and explosive testing interrupted the ongoing cycle of modernization programs, which included both the construction and eventual replacement of existing stockpile weapons with newer designs.

A crucial component of this process was nuclear testing to refine new designs during the development phase, assess the yields of weapons once deployed, and identify and rectify specific technical issues. Without the capability to produce new weapons or conduct tests, the United States confronted the unforeseen challenge of sustaining deterrence through novel and uncharted means.

The National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 1994 mandated that the Department of Energy (DOE) establish a Stockpile Stewardship Program (SSP), employing science-based methodologies and advanced computing, to ensure that the nuclear stockpile remained safe, secure, and effective without necessitating nuclear explosive tests.

Since 1994

All current U.S. ballistic missile warheads were designed and built in the 1970s and 1980s, and their designs addressed specific Cold War problems from the 1960s.

In high stockpile numbers, U.S. nuclear tactics emphasized overwhelming adversary defenses using many weapons since 1994, according to the Department of Energy (DOE). Subsequently, the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) has effectively maintained and upheld the safety, security, and efficacy of the nuclear stockpile without conducting nuclear explosive tests.

Through the advancement of new scientific, computational, and technical tools and methodologies, the Secretaries of Defense and Energy have successfully certified the continued viability of the United States nuclear deterrent annually since 1995, without resorting to nuclear explosive testing.

The United States has not deployed a newly designed nuclear weapon incorporating new nuclear components since 1991.

During this period, the United States also significantly reduced its stockpile. In 1991, the U.S. nuclear stockpile comprised 19,000 nuclear weapons; by 2003, this number had decreased to approximately 10,000, and by 2009, it had further declined to roughly 5,000.

As of 2017, the last year for which the United States published unclassified stockpile figures, the total number of weapons stood at approximately 3,800. Given that the United States has not produced any new nuclear weapons, it has opted instead to extend the operational lifespans of the existing weapons within the legacy stockpile.

Life Extension Programs (LEPs) have been fundamental to the United States’ capability to maintain its nuclear arsenal in compliance with arms control treaties with Russia and internal U.S. decisions regarding the appropriate size of the nuclear deterrent. For additional details on arms control treaties, refer to Chapter 12, Nuclear Treaties and Agreements.

2018 and Beyond

The global security landscape has evolved into a more perilous state than the United States had anticipated following the conclusion of the Cold War. The specter of nuclear competition among Great Powers persists.

While the National Nuclear Security Administration’s Stockpile Stewardship Program (NNSA SSP) has succeeded in ensuring that the existing nuclear stockpile remains safe, secure, and effective, and while the atomic platforms and systems are continuously maintained to ensure operational readiness, the necessity for modernization can no longer be postponed.

The average age of U.S. nuclear weapons stands at 40 years, nearing the end of their life extension or planned retirement—this duration is more than double their original design lifespans.

All life-extended weapons within the stockpile are projected to reach the conclusion of their planned operational lifetimes by the mid-21st century, with some exceeding their intended operational duration by over threefold.

Certain components of these life-extended weapons, such as plutonium pits, have been retained in their original state, resulting in these components remaining in the stockpile for many decades beyond their originally anticipated service lives. They will continue to do so until suitable replacements are developed.

Moreover, U.S. nuclear delivery systems have likewise been maintained beyond their designated service lives.

By 2035

By 2035, every U.S. nuclear delivery system will have surpassed its design life by an average of 30 years.

By 2040

By the early 2040s, all U.S. nuclear delivery vehicles will have reached the end of their operational lifespan. Upon retirement, the air-launched cruise missile (ALCM) and the Minuteman III intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) will have exceeded their 10-year design life by over five years.

The Ohio-class ballistic missile submarine (SSBN) has already surpassed its estimated operational timeframe, while the B-2A bomber and the F-15E dual-capable aircraft will be nearing 40 years of service before retirement. The B-52 bomber is anticipated to be nearing a century of service when it is ultimately scheduled to retire in the mid-2050s.

The Future of Nuclear Deterrent

The U.S. military has effectively operated its nuclear force, demonstrating its success in deterring nuclear warfare—since 1945, no nuclear weapons have been used in combat. Our scientists, engineers, designers, and production teams have meticulously maintained the atomic stockpile, extending the life of U.S. weapons without resorting to nuclear explosive testing.

However, the aging Cold War-era delivery systems and their associated weapons cannot be sustained indefinitely. It is imperative to modernize the nuclear deterrent to prevent the decline in performance due to aging systems—a scenario we refuse to accept.

A modern U.S. deterrent must be responsive to threats and leverage technological advancements, keeping pace with adversaries progressing rapidly. Comprehensive replacement programs are in motion to guarantee no capability gaps when legacy systems become outdated or face obsolescence due to advancements by adversaries.

Conclusion

Nuclear deterrence remains a cornerstone of U.S. national security strategy, bolstered by robust nuclear forces and effective command, control, and communications.

The atomic deterrent will deliver survivable and responsive capabilities, ensuring that adversaries are deterred from attempting a disarming first strike. It will project our resolve through the strategic positioning of forces, clear messaging, and flexible response options.

The United States will be equipped to respond to a wide array of contingencies with tailored options while mitigating risks associated with technological failures and adversary breakthroughs, allowing us to adapt swiftly to changes in the security landscape.